I once met Georgia O’Keeffe. This was not easy to do, and I considered it an achievement.

It was in the early nineteen-seventies, when I was in my early twenties. I

was working at Sotheby’s, in New York, in the American paintings

department. One of the things I did there was catalogue the works that we

sold. I held each picture in my hands, felt its shape and weight. I

measured and described it, recording the medium, condition, signature. The

date. The provenance and exhibition history. I came to know the works very

well.

During this time I had begun to write about American art. I was

particularly interested in the modernists, those early-twentieth-century

artists who were part of the rising tide of abstraction. I wrote about

different members of this group—Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove. I wanted to

write about O’Keeffe, but this was difficult. She held the copyright to

many of her paintings, so it was necessary to ask permission from her in

order to reproduce them. This was one reason that relatively little

scholarship had appeared on her: How could you write a book about art

without using images? Another reason was the confusion that permeated

critical response to her work until well into the sixties. All those

flowers! Was she a great artist or a cheap sentimentalist? The work was so

easy to like—could it be important? She was scorned by the guys, and, if

you wanted to be taken seriously as a scholar, it seemed risky to write

about her.

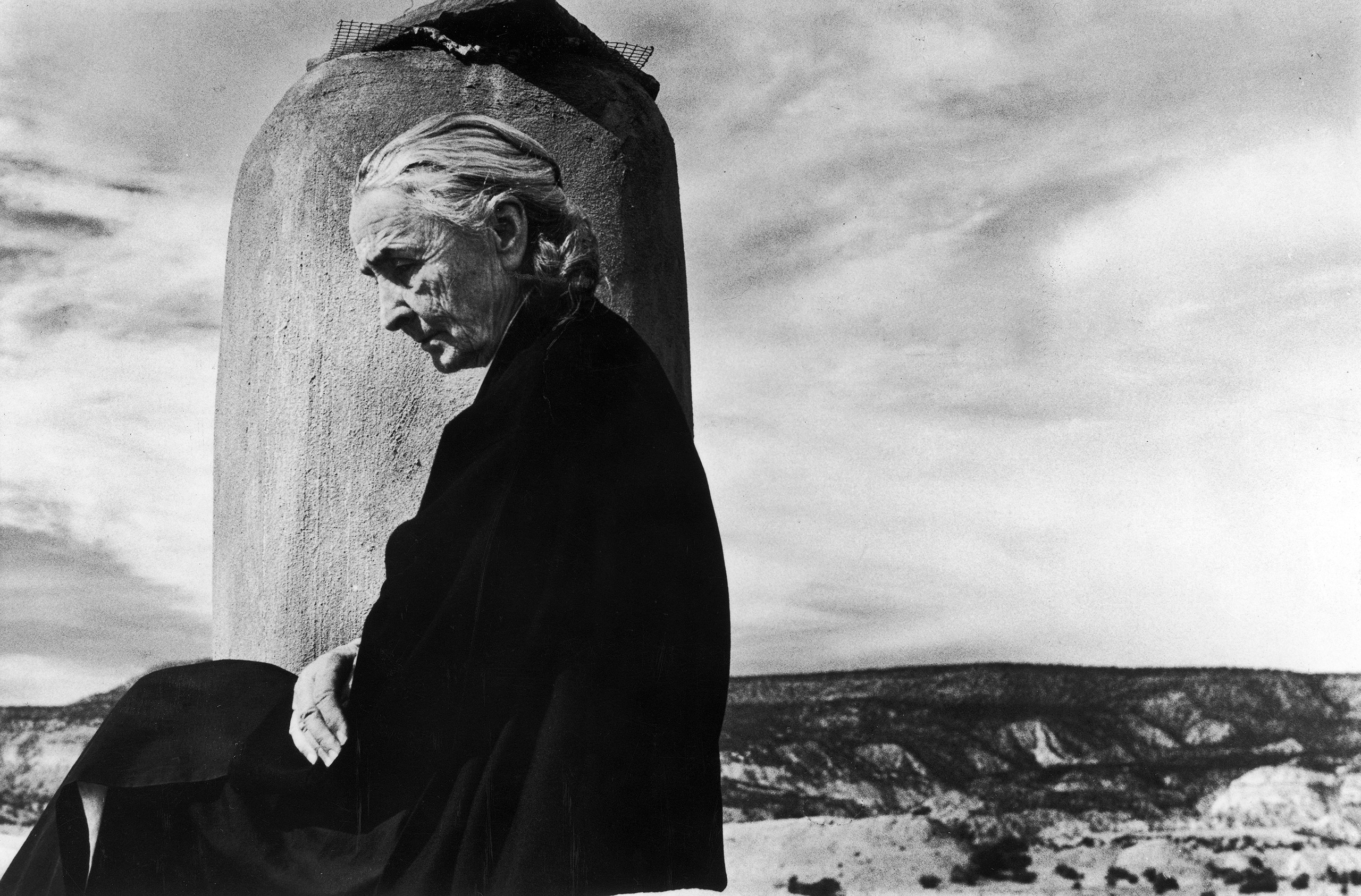

Another reason for the paucity of writing about O’Keeffe was her own

inaccessibility. She lived in a small village in rural New Mexico and

rarely gave interviews. Seclusion and withholding were part of her

persona. She was not interested in publicity, and it is said that she once

refused a request for a one-person show at the Louvre. Here was a paradox:

the work, so intimate and engaging, even accessible, and the artist, so

remote and self-controlled, clothed in severe black and white. The mystery

gave O’Keeffe a kind of charged glamour. A sighting was a significant

event.

That season, Sotheby’s had received an O’Keeffe painting of Canadian

barns. It had been done in the early nineteen-thirties: two dark gray

buildings in a wintry landscape. I catalogued it, and asked Doris

Bry—O’Keeffe’s private agent, who had once been the assistant to Alfred

Stieglitz, O’Keeffe’s former husband—for information on it. Later she

called me. “Mrs. Alger,” she said (for that was my name then), “this is

Doris Bry.” Of course I knew who it was. She had a dry, gravelly voice,

very distinctive, with a Waspy drawl. “I’m calling about the painting of

Canadian barns.”

“Yes, Miss Bry.” I used my formal, fluty, professional tone. “How may I

help you?”

“I’d like to have the painting brought over to my apartment.”

Doris Bry lived in an apartment in the Pulitzer mansion. This was a grand

Beaux-Arts building, only a few blocks away from our offices on Madison

Avenue. But it didn’t matter how close she was. “I’m so sorry, Miss Bry,”

I said, “but our insurance policies don’t permit the works to leave the

premises until they have legally changed hands. If you’d like to bring

someone in to see the painting, I’ll be happy to have it brought out to

the viewing room and put up on the easel. But I can’t allow the painting

to leave our property.”

“Mrs. Alger,” Miss Bry said, “the artist is here. She would like to see

the painting.”

“I’ll be there in ten minutes,” I said, in my normal voice.

I called storage to have the painting brought out. I had it under my arm

and was walking down the hall on my way to the front door when I ran into

my boss.

“What are you carrying?” he asked.

“Canadian barns,” I said, putting a hand over the frame protectively.

“Where are you going?” he asked. “It can’t leave the premises.”

“The artist wants to see it,” I said.

My boss put out his hand. “I’ll take it.”

“I answered the phone,” I said. “I’m taking it.”

With the painting under my arm, I walked down Madison Avenue to the

Pulitzer mansion. Doris Bry ushered me into her apartment. She was a tall,

stately woman, rather ponderous. She had dark eyes, pale, lightless skin,

and a mass of short gray curls. She brought me into the living room, where

there were three other people—two lawyers in dark suits and an older

woman. Bry introduced me.

“This is Mrs. Alger, from Sotheby’s.” The woman nodded pleasantly but said

nothing. She was much smaller than I, which surprised me. She had a lined

face, dark, hooded eyes, and long silvery hair coiled into a low bun. She

wore a gray cotton housedress with a white collar and a narrow self-belt.

On her feet, she wore flat black Chinese slippers, with straps across the

insteps.

Everyone watched as I carried the painting across the room and set it on

the easel. The small woman came with me, but Bry and the lawyers stood at

the back of the room, talking. Georgia O’Keeffe and I stood in front of

the painting. She looked quietly at the canvas, as though it were part of

her, as if she were alone with it.

I stood silently beside her. But that wasn’t enough. When people meet

someone famous, often they want to inflect themselves upon the moment, to

impose their own identities upon that of the famous person. They say, “I

grew up in your town,” or, “I have that same scarf,” or, “I met you once

in a train station.” It’s a hopeless venture.

“I hope you like the frame,” I said. I had ordered it myself. It was a

simple silver half clamshell, the kind that Arthur Dove had used. I knew

O’Keeffe had liked Dove and had admired his work. I knew she’d like the

frame. She’d be grateful. This was my moment.

She answered without turning. “I like them best without frames.”

I said nothing more. She stood looking at the painting, calm and utterly

self-possessed. I think she was wearing a black sweater, a thin little

cardigan, not buttoned up.

She’d have been in her early eighties then.

Nearly twenty years later, in the spring of 1986, I was living in northern

Westchester County. We had moved there ten years earlier, my family and I.

We were out in the country, in an old farmhouse with a big barn and some

fields. Living with us were four or five horses, two or three dogs, and

some large cats. My daughter was fourteen. I had left the art world.

One evening, my husband, Tony, came home from the city and found me in the

kitchen. He was in his business suit, still carrying his briefcase.

“I have something to tell you,” he said. On the train coming out, he’d sat

next to a friend of ours, Edward Burlingame, who was the editor-in-chief

and publisher at Harper & Row. Edward had said, “Georgia O’Keeffe has just

died, and there isn’t a big biography of her. Who do you think we should

ask to write it?”

— Roxana Robinson for The New Yorker, excerpt

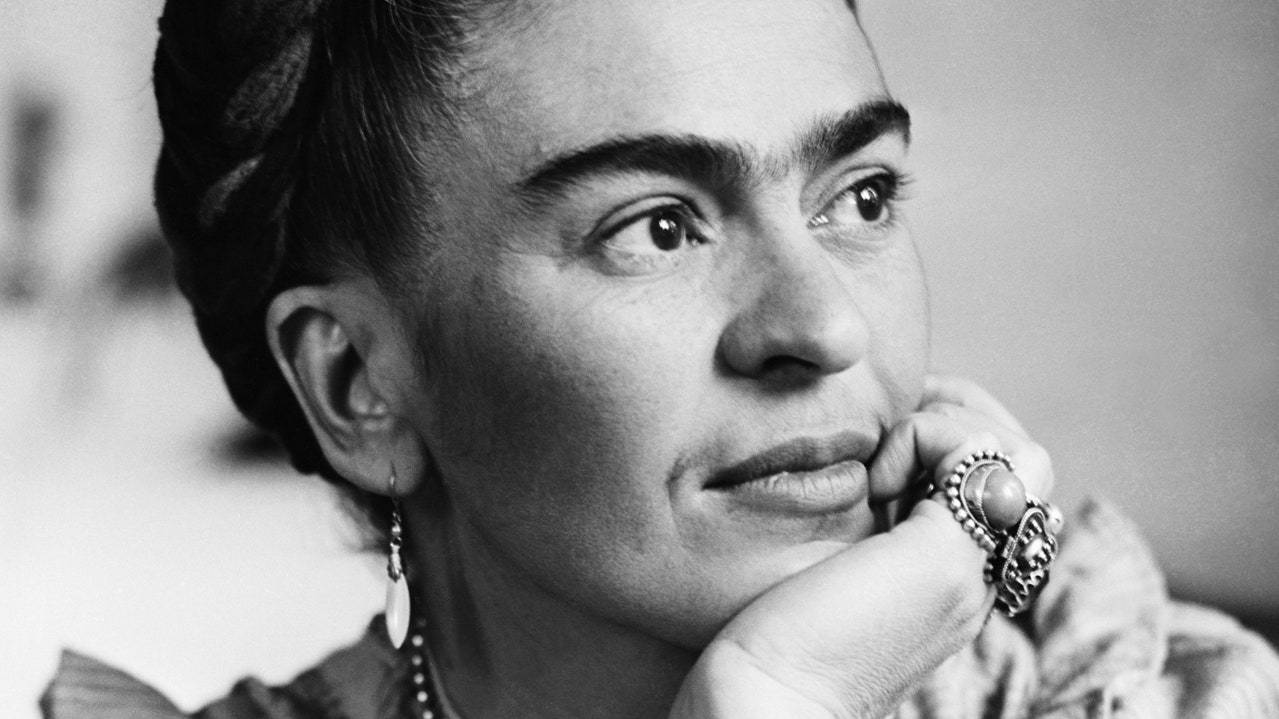

Legendary artist Frida Kahlo spent most of 1950 in a hospital bed in

Mexico City, recovering from a series of spinal surgeries. Her

recuperation involved bed rest, during which her torso was immobilized in

a heavy plaster cast. In a telling contemporary photograph of the painter

and future global feminist icon, she is propped up against her pillows,

embellishing the front of her latest plaster corset with the aid of a hand

mirror and a tiny brush. Her pointy nails are lacquered with dark polish.

Her center-parted hair is pulled back neatly. A pile of satin ribbons and

flowers adorns the crown of her head. She sports dangly earrings, chunky

rings on every finger, and a pair of bracelets.

Regardless of the degree to which she was suffering, Frida Kahlo always

enjoyed the spectacle of herself. She was a playful exhibitionist, a

fervid and erotic provocateur dispatching updates from the land of female

suffering. It was part of what made her difficult: She forced people to

look at her, to share her feelings, when they would prefer to look away.

Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón was born in Coyoacán, a tidy

suburb of Mexico City, in July 1907. Until the day Frida (she dropped the

“e” in 1922) was hit by a streetcar—literally, at the age of 18—nothing in

her upper-middle-class background would disclose her future: that she

would one day become Mexico’s most celebrated painter, a sexy

international art megastar and pop icon who would produce unnerving

masterpieces that would hang in the world’s major museums. Or that she

would “enjoy” a passionate, tumultuous marriage to Mexico’s most famous

muralist and womanizer, Diego Rivera. Frida and Diego married for the

first time in 1929, divorced in 1939, remarried in 1940, and remained wed

until Frida’s untimely death in 1954, at the age of 47. Years after both

artists were dead, a travel squib appeared in the New York Times, which

included the sentence: “Though they created some of Mexico’s most

fascinating art, it’s the bizarre Beauty-and-the-Beast dynamic that has

captivated the world and enshrouded both figures in intrigue.”

— National Geographic, excerpt

WASHINGTON — The exhibition “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” at the

Hirshhorn Museum is great fun if you like to be dazzled by rooms whose

mirrored interiors create countless, ever-diminishing reflections of

themselves and anything in them. And who doesn’t?

The exhibition “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” at the Hirshhorn Museum is

great fun if you like to be dazzled by rooms whose mirrored interiors

create countless, ever-diminishing reflections of themselves and anything

in them. And who doesn’t?

Ms. Kusama, who was born in Japan in 1929, made her first Infinity Mirror

room, “Phalli’s Field,” in New York in 1965, filling the 15-square-foot

floor of a mirrored space with hundreds of her signature stuffed phalli,

or tubers, covered in red-on-white polka-dot fabric. The effect was

glorious, beguiling. And still is: “Phalli’s Field” is the first mirrored

environment in the Hirshhorn show. Step into it and you enter another

world, an eye-popping garden of benign cactuses spreading out in all

directions, or an underwater wonderland of coral or sea anemones.

Over the past several decades, “Phalli’s Field” and the 19 other mirrored

rooms Ms. Kusama has made since have established her as a beloved figure.

Crowds line up around the block to enter her rooms, one person at a time;

absorb their illusionistic, sometimes meditative effects; and step out,

usually after the requisite selfie. Some time ago, she transcended the art

world to become a fixture of popular culture, in a league with Andy

Warhol, David Hockney and Keith Haring, all of whom she preceded and

probably influenced, not least in her grasp of publicity.

The Hirshhorn show is the first to focus so intently on her mirrored-room

environments. Organized by Mika Yoshitake, the museum’s associate curator,

it brings together six of them, more than in any previous show. Evenly

spaced around one of the Hirshhorn’s rings, the rooms have their own

waiting areas, where visitors will line up in manageable numbers, the

museum says, because the show has timed tickets. Depending upon the length

of the lines, each visitor may be permitted only 30 seconds in a room.

The wide fame of Ms. Kusama and artists like her is usually built on

serious art-world street cred. By the time she made “Phalli’s Field,” Ms.

Kusama was already a phenomenon. She had arrived in 1958 and, within two

years, established herself as a major artist in a thoroughly

male-dominated art world.

For more than 50 years, the Japanese ultra-Pop artist has awed audiences

by crafting sculptural illusions with light and mirrors to replicate the

sense of infinity. Experience five rooms at the Hirshhorn Museum and

Sculpture Garden.CreditCredit...Tyrone Turner for The New York Times Ms.

Kusama’s critical triumph was based on her abstract “Infinity Net”

paintings, which she unveiled in her first gallery show, in 1960, along

with the slightly later “Accumulations” sculptures. They first made

manifest the willful intensity in nearly everything she does, as well as

an almost compulsive use of repetition.

The “Net” paintings were among the first to completely absorb and

transform Jackson Pollock’s radical drip paintings. They showed a way

beyond Abstract Expressionism, which was by then dwindling to empty,

overblown gestures. Ms. Kusama reduced them to miniature, possibly

taunting, feminine gestures. She covered expanses of canvas painted a

monochrome of red, green, white or goldenrod yellow with open patterns of

tiny, comma-like strokes — a form of craft, almost, but a very expressive

one — often in marathon work sessions. The background color peeks through,

while the inevitable irregularities of the handmade curls create a

hypnotic, energized field, arguably the best Op Art ever made.

There are four ’60s “Net” paintings at the Hirshhorn, but you can also see

the motif germinating in a clutch of visionary works on paper that Ms.

Kusama made while still in Japan. The “Net” motif was further spurred by

the sight of the Pacific Ocean as she flew to America, and her impatience

with Abstract Expressionism once she got here.

The “Accumulations” sculptures and installations are pieces of furniture

bristling with the stuffed phalli, usually painted white. The results, as

seen at the Hirshhorn in two armchairs from the early ’60s and a 1994

version of a rowboat piece redone in a sparkling violet synthetic fabric,

create a sense of occupation or possession. These objects seem to have

been overtaken by a horde of alien creatures. They announce their

independence from human use while exuding a visual and tactile magnetism.

— Roberta Smith for The New York Times, excerpt