When she looked at you and addressed you by your Christian name, she made

it sound like a promise, one that stood on the side of everything that was

juicy, smart, black, amused, yours. In the old days, when ladies were

“colored” and she herself was just a child, she had learned from those

ladies, probably, the same eye-rolling, close-mouthed look of incredulity

that she employed when she recounted a glaring error of judgment on

someone else’s part, or something stupid someone said or didn’t know they

were about to say. After she gave you that look, you never wanted to say

anything dumb again, ever. If she took you in as a friend—and this was

rare in a world where so many people wanted her time and felt they had a

right to her time, given the intimacy of her voice—she was welcoming but

guarded. Then, if you were lucky enough and passed the criteria she

required of all her friends, which included the ability to laugh loud and

long at your own folly, and hers, too, she was less guarded, and then very

frank: there was no time for anything but directness.

Once she told me that when she was a young single mother raising her two

boys, she would look in on her children as they slept. Here, Toni, the

former student-actress, would clutch at her blouse to convey wonder and

self-sacrifice as she looked down at her children. “This is the view I had

of myself then,” she said, the laughter starting to bubble up in her

chest. Because, the truth is, her kids weren’t having it. Indeed, one of

her boys asked her not to roam around the room like that at night, it

frightened him. And here she would burst out with a laugh that mocked the

very idea of self-perception, let alone self-dramatization: they would

always be knocked down by someone else’s reality.

She was a wonderful conversationalist with beautiful hands; good manicures

were one of her few indulgences after a lifetime of tending to others,

washing dishes, cleaning up, making do. When we first met, in 2002, she

didn’t have to straighten out anyone else’s mess. Like the older women she

described so beautifully in “The Bluest Eye,” she was, by that time, in

fact and at last free. Free from the responsibility of having to please

anyone but herself. She was excited to be herself. When you visited her,

or ran into her at an event, she sat and told stories. She did this

without the benefit of an iPhone to look certain details up. The details

were in her head; she was a writer. As she described this or that, she

drew you in not just by her choice of words but by the steady stream of

laughter that supported her words, until, by the end of the story, when

the scene, people, weather, were laying at your feet, she would produce a

fusillade of giggles that rose and fell and then disappeared as she shook

her head.

More truths: she didn’t like something I wrote about one of her books in

an early piece and she said so. We were sitting in a large, empty

restaurant near her home in Rockland County. She had driven us there with

a speed and force that shocked me, but, then again, why should it have?

She was Toni Morrison. This was one of the first times that we were alone.

(Previously, we always met through friends.) When she said that my

criticism displeased her, I turned around; I truly did not know whom she

was talking to, and told her so. The person who wrote what she didn’t like

was someone I didn’t remember being, someone I no longer identified with,

a person who had probably tried to big himself up because ants always

think they’re taller crawling on the shoulder of giants. After I said some

version of all that, she said that she understood. And then the

conversation began in earnest, but not before I had another shock, this

one of realization: I had hurt Toni Morrison. Somehow, Toni Morrison could

be hurt.

When you were with her, the fabled editor came out, and she saw your true

measure as a person, and what you could do, or what she felt you could do,

because she came up in publishing when editing was synonymous with care. I

think she worried about my tendency to worry and not take up too much

space as a writer, to let others go first, to draw a veil between me and

the world out of shame and fear and trepidation. She had probably seen

this tendency in a number of the women writers she nurtured over the

years, and in some of the gay black male artists, such as Bill Gunn, whom

she had loved, too. (When he was sick with aids, she went to the hospital

to see him with one of her famous cakes. “I knew he couldn’t eat that

cake,” she said. “But he was happy to have that cake.”) So when you

stepped out, she applauded you. Once, I had gone with a friend to have

some shoes made by a cobbler. When the shoes were finished, Toni saw me

wearing them at a dinner party. I told her the story. She looked at me,

beamed, and said, “That’s right, my shoes.”

Boldness can make you lonely, but she never complained of loneliness. She

talked about the world as though it were in conversation with her. I have

yet to meet anyone who could “read” the media with that kind of swiftness

and sanity that she could. She saw the madness we’re living in now years

ago because of certain trends in reporting and in literature. “The

complexity of the so-called individual that’s been praised for decades in

America somehow has narrowed itself to the ‘me,’ ” she said.

As a gorgeous-looking student at Howard University, in the

nineteen-fifties, Toni acted a bit with the Howard Players, a group then

nurtured by our mutual friend, the late, great director and writer Owen

Dodson. He told me what a superb actress she had been, beautiful in form

and voice, and it’s always interesting to me how so many of the women

writers I’ve admired—Jean Rhys, Jamaica Kincaid, Toni—had, without knowing

it, first started to look for themselves, for their writer’s voices, on

the stage. Acting and singing requires the performer to do two things

simultaneously: be themselves and not be themselves but a character,

giving life to a script they did not write.

Of course, that condition is not unknown to women in general, and when

Toni used to say, “I didn’t want to grow up to be a writer, I wanted to

grow up to be an adult,” she was saying a lot. Because being an adult

required a lot, namely taking the human race and one’s role in it

seriously. She wrote what she called “village literature,” for the tribe,

by which she meant black people. To be understood in the diaspora that we

call black life requires a high degree of intellectual alacrity and

technical finesse: black people speak many languages in part because

they’ve had to survive many different kinds of dominant cultures in order

to live, let alone prosper, make things, make a mark. It takes a hugely

ambitious artist to say that I will speak to these people—my people—in a

voice we can all understand, together, just us, and if anyone else wants

to follow, they can. To do that, Toni closed the door on what far too many

writers and artists of color become preoccupied with when they make,

directly or indirectly, “whiteness” their subject. Toni kicked patriarchy

to the curb with barely a backward glance.

Part of the extraordinary power of “Sula” is that it’s a world where men

are not the focus. It’s the sound of women’s voices that takes precedence,

makes the story. About two-thirds through the book, Sula, an artist

without an art, a free colored woman, returns to the town where she grew

up and where she was raised, in part, by her grandmother Eva.

Sula threw herself on Eva’s bed. “The rest of my stuff will be on later.”

“I should hope so. Them little old furry tails ain’t going to do you no

more good than they did the fox that was wearing them.”

“Don’t you say hello to nobody when you ain’t seen them for ten years?”

“If folks let somebody know where they is and when they coming, then other

folks can get ready for them. If they don’t—if they just pop in all sudden

like—then they got to take whatever mood they find.”

“How you been doing, Big Mamma?”

“Gettin’ by. Sweet of you to ask. You was quick enough when you wanted

something. When you needed a little change or . . . ”

“Don’t talk to me about how much you gave me, Big Mamma, and how much I

owe you or none of that.”

“Oh? I ain’t supposed to mention it?”

“OK. Mention it.” Sula shrugged and turned over on her stomach, her

buttocks toward Eva.

“You ain’t been in this house ten seconds and already you starting

something.”

“Takes two, Big Mamma.”

“Well, don’t let your mouth start nothing that your ass can’t stand. When

you gone to get married? You need to have some babies. It’ll settle you.”

“I don’t want to make somebody else. I want to make myself.”

“Selfish. Ain’t no woman got no business floatin’ around without no man.”

“You did.”

“Not by choice.”

“Mamma did.”

“Not by choice, I said. It ain’t right for you to want to stay off by

yourself. You need . . . I’m a tell you what you need.”

Sula sat up. “I need you to shut your mouth.”

“Don’t nobody talk to me like that. Don’t nobody . . . ”

“This body does. Just ’cause you was bad enough to cut off your own leg

you think you got a right to kick everybody with the stump.”

“Who said I cut off my leg?”

“Well, you stuck it under a train to collect insurance.”

“Hold on, you lyin’ heifer!”

“I aim to.”

“Bible say honor thy father and thy mother that thy days may be long upon

the land thy God giveth thee.”

“Mamma must have skipped that part. Her days wasn’t too long.”

“Pus mouth! God’s going to strike you!”

“Which God? The one watched you burn Plum?”

“Don’t talk to me about no burning. You watched your own mamma. You crazy

roach! You the one should have been burnt!”

“But I ain’t. Got that? I ain’t. Any more fires in this house, I’m

lighting them!”

“Hellfire don’t need lighting and it’s already burning in you . . . ”

“Whatever’s burning in me is mine!”

“Amen!”

“And I’ll split this town in two and everything in it before I’ll let you

put it out!”

“Pride goeth before a fall.”

“What the hell do I care about falling?”

The brilliance of this conversation is in its economy and the reality of

the women’s talk: if you grew up anywhere near these types of characters,

it’s like listening to a transcript of dialogue that you’ve heard in the

privacy of your own home, or a relative’s. Sula shows her ass to show her

anger, and then some.

— Hilton As for The New Yorker, excerpt

Seriousness, for Susan Sontag, was a flashing machete to swing at the

thriving vegetation of American philistinism. The philistinism sprang from

our barbarism—and our barbarism had conquered the world. “Today’s

America,” she wrote in 1966, “with Ronald Reagan the new daddy of

California and John Wayne chawing spareribs in the White House, is pretty

much the same Yahooland that Mencken was describing.” Intellectuals,

doomed to tramp through an absurd century, were to inflict their

seriousness on Governor Reagan and President Johnson—and on John Wayne,

spareribs, and the whole shattered, voluptuous culture.

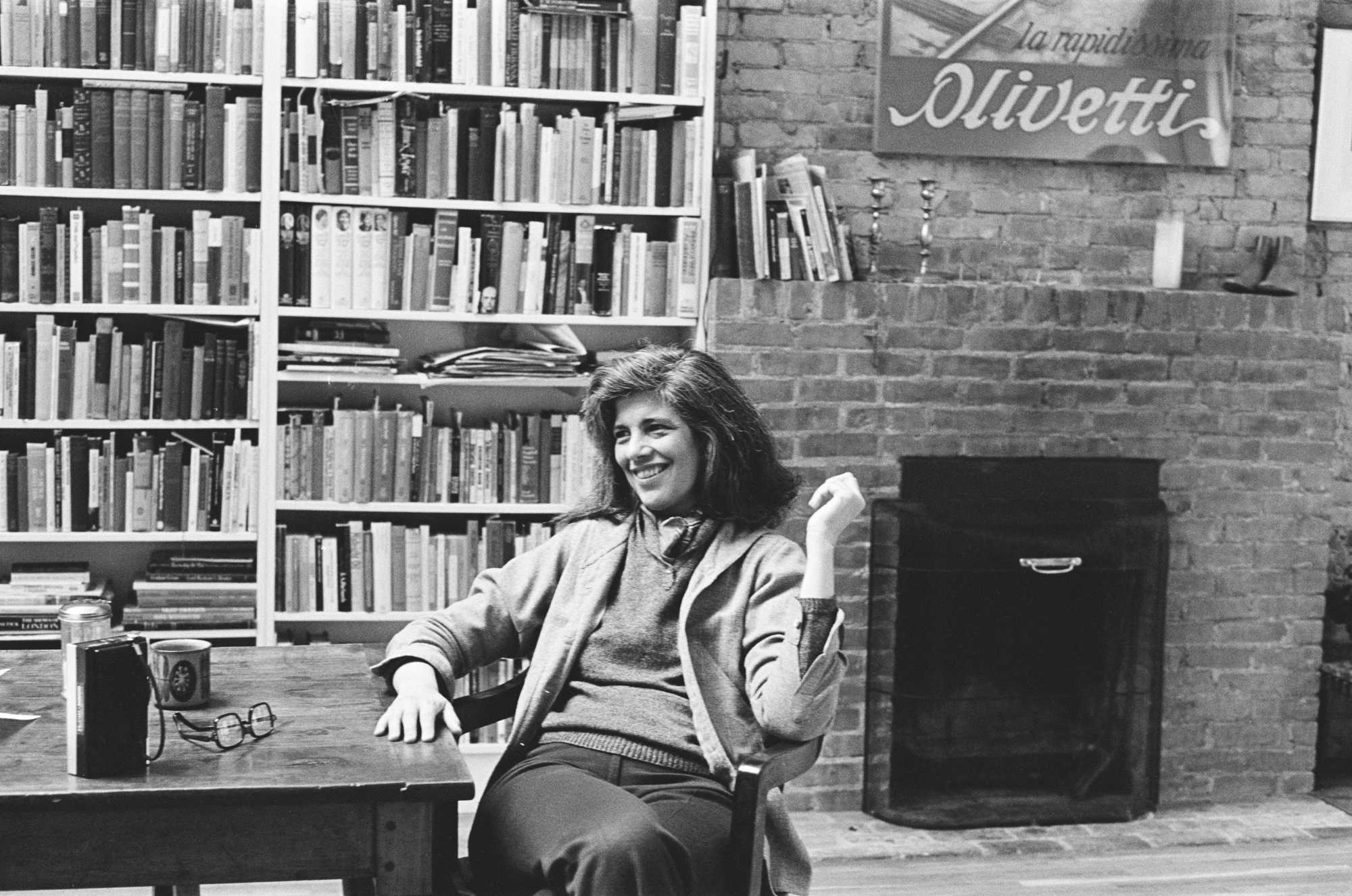

Sontag's nonfiction prizes ardor her fiction is filled with aching

irresolution. Sontag’s nonfiction prizes ardor; her fiction is filled with

aching irresolution.Photograph by Bruce Davidson / Magnum The point was to

be serious about power and serious about pleasure: cherish literature,

relish films, challenge domination, release yourself into the rapture of

sexual need—but be thorough about it. “Seriousness is really a virtue for

me,” Sontag wrote in her journal after a night at the Paris opera. She was

twenty-four. Decades later, and months before she died, she mounted a

stage in South Africa to declare that all writers should “love words,

agonize over sentences,” “pay attention to the world,” and, crucially, “be

serious.”

Only a figure of such impossible status would dare to glorify a mood. Here

was a woman who had barged into the culture with valiant attempts at

experimental fiction (largely unread) and experimental cinema (largely

unseen) and yet whose blazing essays in Partisan Review and The New York

Review of Books won her that rare combination of aesthetic and moral

prestige. She was a youthful late modernist who, late in life, published

two vast historical novels that turned to previous centuries for both

their setting and their narrative blueprint; and a seer whose prophecies

were promptly revised after every bashing encounter with mass callousness

and political failure. The Vietnam War, Polish Solidarity, aids, the

Bosnian genocide, and 9/11 drove her to revoke old opinions and brandish

new ones with equal vigor. In retrospect, her positions are less striking

than her pose—that bold faith in her power as an eminent, vigilant,

properly public intellectual to chasten and to instruct.

Other writers had abandoned their post. So Sontag responded to a 1997

survey “about intellectuals and their role” with a kind of regal pique:

What the word intellectual means to me today is, first of all, conferences

and roundtable discussions and symposia in magazines about the role of

intellectuals in which well-known intellectuals have agreed to pronounce

on the inadequacy, credulity, disgrace, treason, irrelevance,

obsolescence, and imminent or already perfected disappearance of the caste

to which, as their participation in these events testifies, they belong.

She held a contrary creed. “I go to war,” she said a decade after

witnessing the siege of Sarajevo, “because I think it’s my duty to be in

as much contact with reality as I can be, and war is a tremendous reality

in our world.”

Behind the extravagant drama, though, was a shivering doubt. Her work

rustles with the premonition that she was obsolete, that her splendor and

style and ferocious brio had been demoted to a kind of sparkling

irrelevance. The feeling flared up abruptly, both when she was thrilled by

radical action and when she was aghast at public complacency.

“For Susan Sontag, the Illusions of the 60’s Have Been Dissipated”: this

was the smiling headline for a profile of Sontag in the Times. The year

was 1980, a hinge for her, and the article—by a twenty-five-year-old

Michiko Kakutani—was occasioned by the release of “Under the Sign of

Saturn,” Sontag’s fifth book of nonfiction. “Although she maintains that

her current attitudes are not inconsistent with her former positions,”

Kakutani wrote, “Miss Sontag’s views have undergone a considerable

evolution over the last decade and a half.” The gruesome disappointment of

the sixties’ militancy had sent shudders through the left-wing

intelligentsia of which Sontag had once been a symbol.

So the Times piece presented a woman of dignified prudence, whose

deviations are of the mature, domesticated kind. “The sensibility that

resides in this particular town house is an eclectic one indeed,” Kakutani

begins, as the piece swivels like a periscope to survey the gleaming

appurtenances of the life of the mind: the eight-thousand-volume library,

the idiosyncratic record collection, and the portraits of iconic writers

who keep watch over Sontag’s desk like benevolent household gods—Woolf,

Wilde, Proust.

And Simone Weil, the Marxist turned mystic who, during the Second World

War, fled her native France and protested the humiliation of her

countrymen by starving herself to death. In 1963, Sontag had begun an

article on Weil, for the first issue of The New York Review of Books, with

a thundering declaration: “The culture-heroes of our liberal bourgeois

civilization are anti-liberal and anti-bourgeois.” So, at that point, was

Sontag. Weil was a specimen, for her, of a fascinating species: the raving

writer, the flagellant writer, the writer impaled on ruthless principle.

“No one who loves life would wish to imitate her dedication to martyrdom,”

Sontag wrote. “Yet so far as we love seriousness, as well as life, we are

moved by it, nourished by it.”

To love seriousness was to quest for electrifying contact with spiritual

and ideological extremes. The piece on Weil—a woman “excruciatingly

identical with her ideas”—is a hymn to extremity. Extremity shone with the

promise of transcendence, which is why Sontag strapped herself to the

thrashing energies of the sixties. She was enshrined as an intellectual in

revolt, unleashing her polemics on the repressive drabness of “our liberal

bourgeois civilization.” Along the way, she learned, as she put it, “the

speed at which a bulky essay in Partisan Review becomes a hot tip in

Time.” The Weil essay, along with pieces on Alain Resnais, psychoanalysis,

Camus, and Cesare Pavese, appeared in Sontag’s first essay collection,

which in 1966 boomed cannon-like from the prow of the literary left:

“Against Interpretation.”

It was crucial to be against: against fustiness, against the horror in

Vietnam, against the leering excesses and calculated impoverishments of

the global capitalist order. “In place of a hermeneutics we need an

erotics of art”—Sontag’s phrase from the book’s title essay—is now

imprinted on the public imagination because it sent the ecstasies of the

youth movement hurtling toward the arena of aesthetic taste.

I wish I had a house like yours so I could do something nice with it. “I

wish I had a house like yours so I could do something nice with it.”

“Styles of Radical Will,” Sontag’s best book, was published three years

later, and contained an essay on Godard in which she gave full-throated

expression to the spirit of revolution that had swept up the poor, the

dark, the sensuous, and the young. “The great culture heroes of our time,”

Sontag announced, again, “have shared two qualities: they have all been

ascetics in some exemplary way, and also great destroyers.”

This was in 1968—the year she flew to Hanoi and visited the Vietcong,

publishing an account in Esquire. It was the apex of her militant

commitment. Although she had long since turned up her nose at the

“philistine fraud” of the American Communist Party, the North Vietnamese

had inspired her, the struggle filling her mind with a vision of a changed

world. “The Vietnamese are ‘whole’ human beings, not ‘split’ as we are,”

she marvelled.

But, while she was being led around by terse, determined guerrillas, it

struck her that her elaborate American appetites for rock and psychology

and The New York Review of Books were marks of the very luxury she longed,

in those days, to abolish. “I live in an unethical society,” she wrote in

her journal,

that coarsens the sensibilities and thwarts the capacities for goodness of

most people but makes available for minority consumption an astonishing

array of intellectual and aesthetic pleasures. Those who don’t enjoy (in

both senses) my pleasures have every right, from their side, to regard my

consciousness as spoiled, corrupt, decadent.

She yearned to be identical to her ideas, to display the punishing

consistency of Weil, but her ideas jostled and sparked, exploding her

sense of what she was, or wanted to be.

— Tobi Haslett for

The New Yorker, excerpt

Yuval Taylor’s “Zora and Langston: A Story of Friendship and Betrayal” is

an overdue study of the famous yet underdiscussed friendship and literary

collaboration between Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes. “It is so

easy to see how and why they would love each other,” the epigraph, taken

from a 1989 essay by Alice Walker, reads. “Each was to the other an

affirming example of what black people could be like: wild, crazy,

creative, spontaneous, at ease with who they are, and funny. A lot of

attention has been given to their breakup … but very little to the

pleasure Zora and Langston must have felt in each other’s company.”

That final line encapsulates Taylor’s ambitious project. The dramatic

fallout between Hurston and Hughes, triggered by their collaboration on

the ill-fated and controversial play “Mule Bone,” has been fetishized in

literary circles for its dramatic nature. Stories of their heated fights,

rumors of a love triangle involving their typist, Louise Thompson, and the

involvement of lawyers have all made the rounds. Consequently, the

qualities that initially drew these artists together — their shared sense

of mission and pride in ordinary black people — have long been overlooked.

“Zora and Langston” refocuses our attention on the positive aspects of

their relationship, while doing its best to explain — through historical

records and firsthand research — what really brought their friendship to

an end.

In July 1927, Hurston and Hughes embarked on a tour of the Deep South —

part business, part pleasure — which began with a chance meeting in

downtown Mobile, Ala., where the two ran into each other outside the train

station. Hurston was there to interview Cudjo Lewis, the last living

former slave born in Africa; Hughes was giving readings and performing his

own research. Hughes, a Northerner, was out of his element, while the

Alabama-born and Florida-bred Hurston was firmly in hers, traveling with a

gun in her shoulder holster. On this trip, Hughes and Hurston grew

conscious of their shared interest in black folklore and everyday people,

and their pronounced taste for adventure. This chance encounter kicks off

the book’s most exciting chapter, imbued with the “pleasure” Hurston and

Hughes inspired in each other.

Soon after their meeting, the book describes the pair enjoying a meal of

fried fish and watermelon. While most black people would have recoiled at

such a meal because of its evocation of racial stereotypes, Hurston and

Hughes reveled in defying such expectations. They visited Booker T.

Washington’s Tuskegee University, where the only surviving photographs of

Hughes and Hurston together were taken, the pair smiling on campus and

looking impossibly young and carefree — a highlight of the book’s somewhat

anemic visual offerings.

Charlotte Osgood Mason, a white Manhattan socialite and philanthropist who

took on both Hughes and Hurston as a patron at nascent points in their

careers, was a central figure in both their friendship and their

subsequent estrangement. Mason was introduced to both artists by the

academic Alain Locke, whose 1925 anthology “The New Negro” defined the

Harlem Renaissance and cemented his position as its “dean.” Locke was gay

but in the closet, and he and Hughes entered into a correspondence that

culminated in Locke showing up at Hughes’s flat in Paris. Nothing happened

— Locke’s infatuation was probably only semi-requited — but he nonetheless

ensured Mason’s patronage of Hughes, and Hughes, in turn, recommended

Hurston to Mason.

Mason was a major collector of African art who espoused primitivist views

— in vogue at the time— to an uncomfortable degree. She believed

African-Americans and Native Americans were “younger races unspoiled by

white civilization.”Her philanthropy was fueled by the idea that American

culture could be re-energized by exposing it to these “primitive” ones.

True to her views, Mason demanded complete devotion from her Negro

clients, who she insisted call her “godmother.” Mason provided Hughes and

Hurston with generous monthly stipends, but consequently considered

Hurston’s work her property. Hurston wasn’t even allowed to show anyone

her work without Mason’s permission. Surprisingly, Hughes was the first to

break ties with Mason, while Hurston remained on friendly terms with Mason

for most of the rest of the elder woman’s life.

Mason’s stewardship is one of the most glaring and fascinating

contradictions in “Zora and Langston,” simultaneously echoing those at the

heart of both writers’ legacies. Although demeaning, Mason’s patronage

allowed Hurston and Hughes to produce some of their most enduring works.

It also sustained them through low points in their careers, as well as

through the Great Depression, when many of their confreres drifted into

obscurity.

Chief among the book’s strengths is that it does not shy away from

pointing out similar contradictions in the relationship at its heart.

While that eventually reached an explosive end, Hurston and Hughes shared

many years of peaceful and rewarding friendship. The book presents several

possible explanations for their falling-out: Hurston’s jealousy (whether

romantic or platonic remains unclear) of the relationship between Hughes

and Thompson, the beautiful, young aspiring writer hired by Mason to be

their secretary; disagreements over the authorship of “Mule Bone” (Taylor,

a book editor and the author of “Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy From

Slavery to Hip Hop” and “Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular

Music,” sides with Hurston, who claimed to be the play’s principal

author); and miscommunication caused by delays in correspondence.

The book also reproduces the admiring letters Hurston and Hughes sent to

their “godmother,” whose fawning obsequiousness is enough to make one’s

skin crawl. At key moments throughout the book, Taylor takes care to

remind his readers that although both writers were pioneers who brought

blackness into the literary canon, they simultaneously contributed to the

adoption of negative stereotypes about African-Americans. Unfortunately,

this idea appears reinforced by their long, mostly subservient

relationship with Mason.

During their tour of the Deep South, Hurston and Hughes visited the family

plantation of the Harlem Renaissance poet Jean Toomer. There they met one

of Toomer’s distant relatives, who reminded Hughes (as he later recalled

in his autobiography) of Uncle Remus, the folk character once used to

justify the practice of slavery. Hughes became enamored of the man’s hat

and, in the end, Hurston paid $3 to keep it. The Remus story is one of

several revelatory details Taylor highlights in his layered portrait of

these two artists. As Taylor correctly concludes, Hurston and Hughes were

the first American writers to create great bodies of work that were

unmistakably — and proudly — black. The corpus of African-American

literature that has grown in their wake owes them a great deal.

However, their delight in the concept of blackness could occasionally veer

into the exploitative, sometimes propagating negative stereotypes of black

people. Their legacies should account for both tendencies, and the

greatest feat of “Zora and Langston” perhaps lies in Taylor’s loving yet

evenhanded portraits of both figures. There are times when Taylor tries to

be too balanced. After all, Hurston famously expressed troubling political

views, including her insouciant Red-baiting and her critique of the 1954

Brown v. Board of Education decision. Taylor largely excuses these,

attributing the backlash Hurston received to her unpopularity with the

more politically engaged writers of the era. He meanwhile draws a false

equivalency with Hughes’s and Hurston’s attitudes toward whites. All of

this is belied by much of the evidence presented in the book itself. And,

not to mention, Taylor’s analysis would also surely have benefited from a

more probing critique of the sexism inherent in Hurston’s reception during

her lifetime.

None of these minor flaws detract from the book’s overall achievement. It

is a highly readable account of one of the most compelling and

consequential relationships in black literary history, and the time is

ripe for this story to reach a new generation of readers.

— Zinzi Clemmons for The New York Times, excerpt